Let's start with a bit of history

Since the mid-1800s, women have fought hard for equal treatment to men in all aspects of life. The suffragette movement here in the UK really began to gain momentum in the early 1900s when Emmeline Pankhurst founded The Women’s Social and Political Union in 1903, and by 1928 all women over the age of 21 were given the right to vote.

Unfortunately, around this same time, although women were participating in sports, they faced significant obstacles. In 1921, The FA declared that football was “quite unsuitable for females” and banned women from playing on FA association grounds. This ban was not lifted until 50 years later in 1971, when women were finally allowed to form their own affiliated teams and leagues.

Women’s sport really started to take off in the 1990s as more funding and recognition gradually led to women’s sports becoming socially acceptable, and the Equality Act finally recognised the right of women to have their own sports category on the grounds of safety and fairness as recently as 2010.

PRESENT DAY PROBLEMS

Women now have equal rights to men in all aspects of society. However, ‘equal’ does not mean that we are the same; there are undeniable physiological differences between male and female bodies that significantly affect sports performance. These scientific distinctions are why women need their own sex-based category in sports.

It all seemed to be going pretty well for women and girls sports until fairly recently as more ‘transgender’ athletes have entered the women’s sporting arena. The issue for females is whether or not trans-identifying males retain their male physical advantages, making their inclusion in women’s events unfair and potentially dangerous.

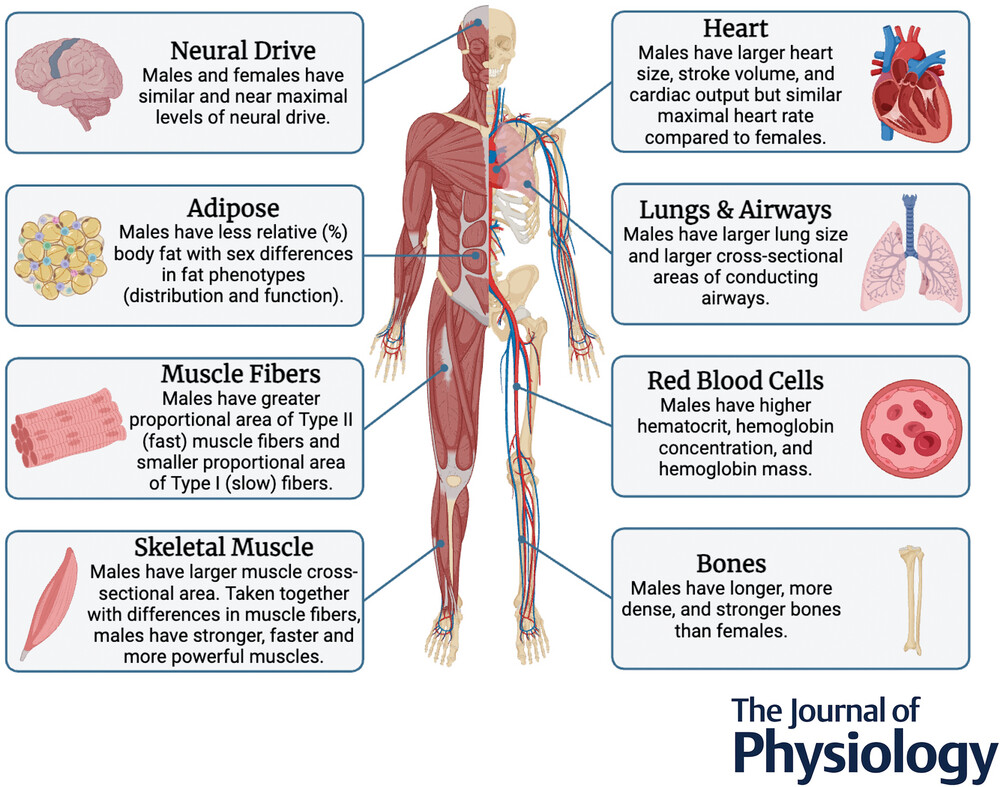

It’s widely accepted that males possess physical advantages compared to females when it comes to athletic ability. Numerous studies and textbooks on anatomy, physiology, exercise physiology, and fitness testing all affirm that these performance variations stem from biological sex differences.

Males typically have greater height and lean body mass, less body fat, higher bone mineral density, larger hearts and lungs, higher VO2 max, and increased circulating haemoglobin levels, among other anatomical and physiological traits that give them athletic performance advantages.

Let's dig a little deeper into these differences...

Muscle Mass and Strength

Males generally have more muscle mass due to higher levels of testosterone, which promotes muscle growth. This typically translates to greater strength, power, and speed in activities like sprinting, weightlifting, and throwing.

- Men typically have 30-60% higher muscle strength than women

- Men typically have 40-45% more lean body mass than women

Body Composition

Males typically have less body fat and more lean body mass than females. Lower body fat can be an advantage in sports where weight is a factor, like swimming or cycling, where less body fat can mean less resistance or drag.

An analysis of 10,894 European individuals, ranging from 18 to 81 years old, shows that:

- On average, men have 3.5 lbs (1.6 kg) less body fat than women

- On average, men have 36.6 lbs (16.6 kg) more lean body mass than women.

Bone Structure

Males tend to have denser bones with larger cross-sectional areas, which can contribute to greater structural strength and less likelihood of bone injuries. Females, in comparison, have a more fragile bone structure which is particularly relevant in contact sports like Boxing, and MMA, or high-impact activities. Studies have shown that in a male and females of the same body weight, the male will have 162% greater punching power. Couple this with the more delicate female bone structure and it’s easy to see why men punching women could be very dangerous and why women need their own sex-based category in sports.

- The average height of Western men is 5’10” (177.8 cm) with an average weight of 200 lbs. (90.7 kg)

- The average height of Western women is 5’5” (165.1 cm) and 170 lbs. (77.1 kg).

If we look at height and body composition together, men typically have 6% less body fat and 42% more lean mass, spread over an additional 8% in height compared to women. In sports such as swimming, volleyball, and basketball, height provides an advantage, and a core principle of exercise science states that greater lean body mass enhances athletic performance.

Pelvis Shape

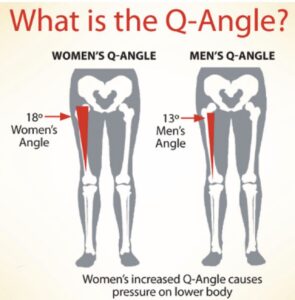

The difference in pelvis shape between males and females also plays a significant role in sports performance.

The female pelvis, designed for childbearing, is generally wider and shallower than the male’s, which is narrower and taller. This difference affects the angle at which the femur (thigh bone) connects to the pelvis, known as the Q angle. A wider pelvis in females leads to a larger Q angle, which can result in less efficient stride mechanics compared to males. This is particularly relevant in running and cycling, where a narrower male pelvis allows for a more direct power transfer and a potentially more efficient stride or pedal stroke.

A wider pelvis in women can restrict stride length during running, which might impact speed. On the other hand, men’s narrower pelvises enable longer strides, which is certainly an advantage in sprinting.

The Q angle differnce also means that men can typically maintain a higher stride rate because their more direct alignment from hip to foot allows for a more efficient force application.

The increased Q angle in females is associated with a higher incidence of knee injuries, especially anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) tears. This is particularly noted in sports involving quick changes of direction, jumping, or contact like football or basketball. The alignment of the knee, influenced by pelvic shape, can result in greater strain on the knee joint during these activities.

As we’ve already established, men typically have a higher muscle mass relative to their body weight, and paired with a pelvis better suited for walking and running, this can provide them with an advantage in sports that demand explosive power or strength, like weightlifting, sprinting, or jumping events.

Heart Size

Males typically possess larger hearts and lungs compared to females. The heart in males is generally larger, not just in overall size but also in the volume of each chamber. This allows for greater stroke volume, which is the amount of blood pumped with each heartbeat.

A larger heart also means that men have a higher cardiac output, which is the amount of blood the heart can pump per minute. This enhances the delivery of oxygenated blood to muscles during physical exertion.

Lung Size

In terms of the lungs, men have larger lung volumes, including total lung capacity, vital capacity (the maximum amount of air that can be exhaled after a maximum inhalation), and tidal volume (the amount of air moved into or out of the lungs during normal breathing).

Larger lungs mean a greater surface area for gas exchange, allowing more oxygen to be absorbed into the bloodstream and more carbon dioxide to be expelled. This efficiency in oxygen exchange is vital for endurance sports where oxygen demands are high.

These anatomical differences contribute to a higher VO2 max in males, which is the maximum rate of oxygen consumption measured during incremental exercise. VO2 max reflects the cardiorespiratory fitness level and is a key determining factor of endurance capacity.

The higher VO2 max in males gives them a competitive advantage in aerobic activities, including long-distance running, cycling, and swimming, where the body’s ability to sustain energy production through oxygen utilisation is critical.

These physiological differences in cardiovascular and respiratory systems can significantly impact performance, giving males an edge in endurance-based sports. Again, this highlights why women need their own sex-based category in sports.

Haemoglobin Levels

Males usually have higher levels of haemoglobin, which carries oxygen to muscles. More efficient oxygen delivery can enhance endurance and recovery, which is beneficial in sports like marathon running or any prolonged physical activity.

Ligament and Tendon Structure

Males often have thicker ligaments and tendons, which can provide better stability and less risk of injuries like sprains or tears, especially in sports involving sudden movements or changes in direction.

Hormonal cycles in females can influence ligament laxity, potentially increasing injury risk, particularly during certain phases of the menstrual cycle when oestrogen levels peak.

Neuromuscular Coordination

Neural drive appears to be similar between the two sexes, but there’s some evidence suggesting that males might have slight advantages in neuromuscular coordination due to differences in brain structure. This could improve reaction times and motor control in some sports.

Endurance vs. Strength

While males generally excel in strength and power activities, females should, at least in theory, have a slight advantage in endurance activities due to higher type I muscle fiber density. However, in practice, this is countered by the previously mentioned cardiovascular advantages in males.

This can been seen in the current world record times for the men’s and women’s marathon:

-

MenKelvin Kiptum of Kenya set the men’s record at 2 hours and 35 seconds at the 2023 Chicago Marathon.

-

WomenRuth Chepng’etich of Kenya set the women’s record at 2 hours, 9 minutes, and 56 seconds at the 2024 Chicago Marathon.

The average gap between men’s and women’s marathon times is around 11.2%.

What about Kids?

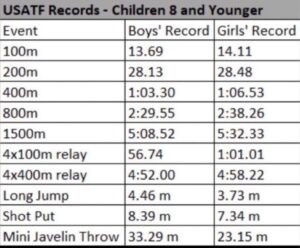

Before puberty, there’s less definitive evidence of performance differences between boys and girls in sports, mainly because activities at this age tend to emphasise recreation and basic skill acquisition. Nonetheless, fitness assessments in children as young as 3 years old indicate that boys generally outperform girls of the same age in tasks involving throwing, muscular strength, muscular endurance, and aerobic fitness.

Boys and girls have different physical abilities even before they hit puberty. Boys usually run faster, jump higher, and have more muscle strength than girls their age. These differences aren’t as big as they get after puberty, but they still matter when it comes to sports or competitions.

Boys and girls have different physical abilities even before they hit puberty. Boys usually run faster, jump higher, and have more muscle strength than girls their age. These differences aren’t as big as they get after puberty, but they still matter when it comes to sports or competitions.

As puberty progresses and testosterone levels in males increase significantly, the performance gap between males and females widens, with males outperforming females by approximately 10-60% in various measures of physical fitness and sports performance into adulthood.

Where do Trans-Identified Males fit into this?

A key point to consider when discussing the inclusion of trans-identified males (transwomen) in women’s sports is the well-documented fact that adult males generally have athletic advantages over adult females, as previously noted. Where the performance can be easily and equally quantified for comparison, such as swimming, track and field, powerlifting, weightlifting, speed skating, and cycling, males are faster, jump higher, throw farther, and lift more weight than females.

By mid-puberty, males generally surpass similarly aged, talented, and trained females by 10-60% in athletic performance, with variations depending on the sport. The smallest performance gaps are seen in running and swimming, while the largest are in weightlifting and baseball pitching. In weightlifting and powerlifting, where athletes compete based on body weight, males still outperform females by approximately 30%.

There’s no escaping the fact that transwomen have male anatomy and physiology. The male advantage is present before puberty and increases dramatically once puberty has taken place.

After puberty, even with testosterone suppression and oestrogen administration in transwomen, the biological advantages gained during male development, such as increased body mass, larger heart and lungs, Q angle, and height, do not disappear.

Moreover, the performance differences, like superior muscle strength and running speed, are only minimally reduced.

- Men typically have 30-60% higher muscle strength than women – testosterone suppression reduces muscle strength by 0-9%.

- Men typically have 40-45% more lean body mass than women – testosterone suppression reduces lean body mass by ~4-5%.

So, even if they go through surgical procedures and take hormonal therapies, transwomen retain certain competitive advantages.

CONCLUSION:

The numerous anatomical and physiological differences between males and females highlight why, to ensure fairness and safety, women and girls need their own sex-based category in sports.

Having established that transwomen retain their male anatomical and physiological advantages, their inclusion in the women’s category is both unfair and potentially dangerous to women and girls.

References & Further Reading:

- Bassett AJ, Ahlmen A, Rosendorf JM, Romeo AA, Erickson BJ, and Bishop ME. The Biology of Sex and Sport. JBJS Rev 8: e0140, 2020.

- Brown GA, Orr T, Shaw BS, and Shaw I. Comparison of Running Performance Between Division and Sex in NCAA Outdoor Track Running Championships 2010-2019. Med Sci Sports Exerc 54: 1, 2022.

- Bartolomei S, Grillone G, Di Michele R, Cortesi M. A Comparison between Male and Female Athletes in Relative Strength and Power Performances. J Funct Morphol Kinesiol. 2021 Feb

- Mascherini G, Castizo-Olier J, Irurtia A, Petri C, Galanti G. Differences between the sexes in athletes’ body composition and lower limb bioimpedance values. Muscles Ligaments Tendons J. 2018 Apr

- Hunter SK, S Angadi S, Bhargava A, Harper J, Hirschberg AL, D Levine B, L Moreau K, J Nokoff N, Stachenfeld NS, Bermon S. The Biological Basis of Sex Differences in Athletic Performance: Consensus Statement for the American College of Sports Medicine. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2023 Dec

- Cheuvront SN, Carter R, Deruisseau KC, Moffatt RJ. Running performance differences between men and women:an update. Sports Med. 2005

- Handelsman DJ, Hirschberg AL, Bermon S. Circulating Testosterone as the Hormonal Basis of Sex Differences in Athletic Performance. Endocr Rev. 2018 Oct

- Lewis DA, Kamon E, Hodgson JL. Physiological differences between genders. Implications for sports conditioning. Sports Med. 1986 Sep-Oct

- Kraemer, W. J., et al. (1992). “Hormonal responses to heavy-resistance exercise in humans.” Sports Medicine, 13(4), 245-256.

- Should Transwomen be allowed to compete in Women’s Sports

- Hunter, S. K. (2016). “Sex differences in human fatigability: mechanisms and insight to physiological responses.” Acta Physiologica, 218(4), 250-271.

- Goble, D. J., et al. (2012). “Sex differences in the association of cortical thickness with motor performance.” Behavioral Brain Research, 228(2), 377-382.

- Huston, L. J., et al. (2001). “Gender differences in the biomechanics of jumping.” American Journal of Sports Medicine, 29(1), 30-36.

- Murphy, W. G. (2014). “The sex difference in haemoglobin levels in adults – mechanisms, causes, and consequences.” Blood Reviews, 28(2), 41-47.

- Bassett Jr, D. R., & Howley, E. T. (2000). “Limiting factors for maximum oxygen uptake and determinants of endurance performance.” Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, 32(1), 70-84.

- Lewis CL, Laudicina NM, Khuu A, Loverro KL. The Human Pelvis: Variation in Structure and Function During Gait. Anat Rec (Hoboken). 2017 Apr

- Seeman, E. (1997). “From density to structure: Growing up and growing old on the surfaces of bone.” Journal of Bone and Mineral Research, 12(4), 509-521.

- Wells, J. C. (2007). “Sexual dimorphism of body composition.” Best Practice & Research Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 21(3), 415-430.

- Ofenheimer A, Breyer-Kohansal R, Hartl S, Burghuber OC, Krach F, Schrott A, Wouters EFM, Franssen FME, and Breyer MK. Reference values of body composition parameters and visceral adipose tissue (VAT) by DXA in adults aged 18-81 years-results from the LEAD cohort. Eur J Clin Nutr 74: 1181-1191, 2020.

- Hilton EN and Lundberg TR. Transgender Women in the Female Category of Sport: Perspectives on Testosterone Suppression and Performance Advantage. Sports Med, 2020.

- Klaver M, de Mutsert R, Wiepjes CM, Twisk JWR, den Heijer M, Rotteveel J, and Klink DT. Early Hormonal Treatment Affects Body Composition and Body Shape in Young Transgender Adolescents. J Sex Med 15: 251-260, 2018.